|

||||

|

House Chores for Men and Stay at Home Dads

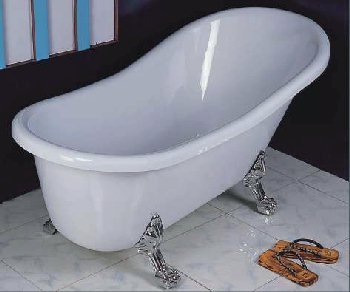

By Charles Moffat - November 2007. I cleaned the bathtub and the toilet today, and indeed much of the bathroom. That's right, a grown man on his hands and knees scrubbing away at the filth, smelling like Lysol and Pine-Sol by the time he is done. The fact that I cleaned the bathroom will no doubt be noticed by my girlfriend who will notice I also rearranged all her shampoos and soaps. Thus it will be an inescapable fact. However this is not the first time I've done this task. Despite the rumours that men don't know how to clean the bathroom there are those who do (and not just clean freaks and germophobes like Jerry Seinfeld). I have routinely cleaned the bathroom in the past and my loving and observant girlfriend has noticed it in the past too, but somehow fails to remember that I do these things when we argue. I think its because, stereotypically, our roles have been laid out for us by the nuclear-family-ish ideas that have been handed down to us by the generations. Men don't clean bathrooms because that is a woman's job right? Men go to work and put the proverbial bread on the table. So during an argument using the one liner "I cook and clean for you, etc, etc." suddenly becomes a moot point because I do cook and clean. There is one very important difference however: Pride and visibility. I don't like my girlfriend around when I clean, because I know what happens. She complains about my methods. "You're not doing it properly!"

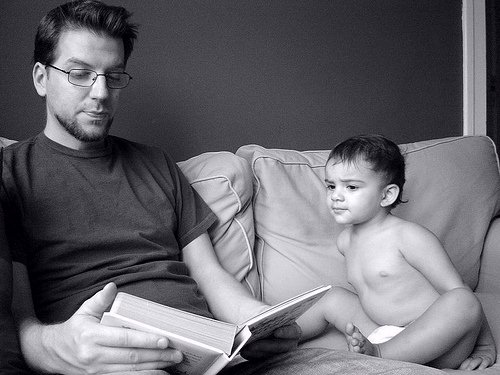

Notice that I can't make that claim when she cooks and cleans because as far as she is concerned she is doing it PROPERLY, and this is an indisputable fact in our household. No point arguing over who is doing it the right way or the wrong way. Thus I prefer to do it when she's not around, like today. She can't complain about the technique if all she sees is the results. Call me what you want: Stay-at-home dad, male homemaker, etc. This is not my day job, of course. My contract for my latest job is simply up. So if I am home and unemployed for the time being I might as well make myself useful. I am a bit of a workaholic and being at home means I have a lot of free time. Being unemployed can be a bit embarrassing for a man, especially if the woman is paying for all the bills. Some men glory it and sponge off their female partners and we call them names like "Lazy bums" and say things like "Why don't you get a job?" Yet truth be told if a woman is going through financial difficulty and the man pays all the bills we don't bat an eyelash. This is frankly because we ASSUME that the woman is performing "wifely duties" at home such as cooking and cleaning, whereas a man in the same situation is likely watching football on TV and drinking beer all day. That is the stereotype after all. And this concept isn't limited to cooking and cleaning. We also assume that men don't know how to deal with children either. In recent years there has been a big increase in the number of fathers dropping out of the workforce to raise their children. It marks a significant social change with the stay at home dad being seen less and less as an oddity. "Let's not kid ourselves: A man at home with an infant is out to sea without a compass. Confusion and disorientation set in. How much to feed? How much sleep do they need and when? The baby doesn't know. You sure as hell don't know. And so the little thing shrieks, flushes crimson, gasps for air. You grow frightened. Fear gives way to weariness. Then, like a heel, you close the door and walk away." says reporter-turned-househusband Charlie LeDuff. The adjustment can be rough, but some of these men discover at-home parenting creates a better life balance and more meaning. Now I am not saying I am ready to start making babies (I want to wait until I am financially set before going down that road), but I am saying there is certainly the feeling that men simply don't know how to handle babies and children. That we are somehow inept. I believe however that WE ARE ALL INEPT when we first become parents. None of us know the first thing about parenting and we're bound to make mistakes. There will be moral questions we have to ask ourselves too as we become parents, like whether we will spank our kids or pull their ears when they are misbehaving. Now I do have some experience in this matter. My father spanked me and my mother would pull my ear, and quite frankly it worked. I am still against parents outright beating their kids however. There is no lesson to be learned by brutalizing your children and sticking them in a hospital.

But a sharp tug on the ear I can appreciate. It is painful and it is embarrassing. Years ago I was an English teacher in South Korea and was assigned a class of preschoolers about 4 or 5 years of age. One of the students kept misbehaving in class, hitting other students and being generally disruptive. I tugged his ear and said "Hajima!" (Don't do in Korean). He cried for like five minutes and I felt very guilty about it, but afterwards he behaved properly and even started to learn. When I told one of the Korean teachers she told me "Next time pull his ear even harder!" That sounds fairly harsh, I admit, but Koreans are very conservative about these matters. A lot worse than ear pulling goes on at both the schools and the homes over there (ie. Getting whipped by a meter long ruler). That kid got off lightly in the end. I don't know whether I will resort to such tactics when I have kids, but I am highly concerned about spoiling them. I have seen first hand what spoiled children end up like and its a growing epidemic (See Nanny 911). Part of the reason some critics would say is because too many parents are both working these days and their kids are alienated and left alone for hours per day. The children are left with the television (the emergency babysitter) on and with free reign of the house. We could blame women for having careers for this trend, but we can also blame delinquent husbands who are rarely ever home. So to me this matter of stay-at-home dads is a natural evolution of things. It is a balancing act as men learn to shoulder their share of the parenting burden. If they don't learn how to be a parent (and let's face it some fathers never really do because they aren't there so often) then its no surprise that their kids grow up to be spoiled and have bahaviour problems because there is no responsible rolemodels. As much as television tries to fill the role I'm sorry, but watching Homer Simpson screw up and then try to make it better is not positive parenting. Its a forgiveness routine for parents who never bothered to learn parenting skills, in the hopes that their children will forgive them after they grow up feeling alienated. As much as we'd all like to have careers it is also important to gauge what is important to us in life: Our kids or our career?

This has been a question that women have been dealing with since they joined the workforce, and they have tried to balance those two options as best they can (sometimes because they have no choice thanks to being a single parent). Now that some men are starting to leave the workforce to be better parents we need to stop and evaluate those roles we generally expect women to fulfill. Starting with cleaning the bathtub and the toilet. You may not like the method he uses to clean it, but do you really want to come home from a hard day at the office and clean it over again yourself? Not likely. Nobody wants to do house chores after work (hence why a lot of people eat out these days or order pizza). In conclusion scrubbing the bathtub gave me time to think.

Safe CounselI have a book on my shelf called "Safe Counsel". It is very old and falling apart, not surprising since it was written in 1894. It outlines advice for young people, both men and women, on how to find a mate, how to be a good husband, raise proper children, etc. A lot of what is in the book is ridiculously racist and sexist by todays standards (especially the section on proper breeding and how you shouldn't marry men with soft hands because they are lazy and selfish, etc.), so ridiculous it makes for a funny read. In one of the sections on how to be a good husband it says that a man must be self-supporting (and a paragraph explaining why), but in the section for how to be a good wife it points out that "behind every good man is a good woman". A paradox to be sure. So a man must be self-supporting, but he can only be good if there is a woman supporting him? Hmm. We understand of course what they are trying to say, but why can the rules not be reversed? Behind every good woman is a good man perhaps? Or a woman must be self-supporting? It makes you realize how much our society has changed in the last 113 years, and how much more we have yet to do.

|

|

|||

|

|

||||

On life as a stay-at-home dad

By Charlie LeDuff. Before my daughter was born, men my age were happy to lather on the unsolicited advice about what being a dad would be like. I would eventually come to find that it wasn't really advice at all, but rather a sort of superficial observation, masculine margarine about what it feels like to be the Fatherly Influence. I would come to realize how little these freelance counselors knew about their own children. "For the first seven months, they're pretty much just digestive tracts," said one friend, whom I shall call Mr. Half-at-Home. "It's the most meaningful thing that will ever happen to you," said Mr. Oprah's Book Club. "To tell you the truth, I can't wait to go to work in the morning," said Mr. End of His Rope. Of course, five days a week these men pack off and dutifully trudge to a desk somewhere, though a few of them aren't necessarily chained to that desk. There's a certain sort of man I know, for instance, who is a writer for a big, sometimes meaningful publication. And from my perspective, sitting here in Los Angeles at noon, still in my underpants, he just may be the most envied creature in all of manhood. I imagine him now off in the bush meeting with some aggrieved group of third world rebels or drinking good wine in a European capital with a certain minister of something or other. Maybe he's beating it across a Latin American border with a group of barefoot migrants or meditating over a body of water in a South Asian jungle. Wherever he may be, I am consumed by him and his adventures. You see, I was once one of his species, a jet-set correspondent for The New York Times. One week I'd be in the Arctic Circle watching Eskimos prepare for a whale hunt; the next I'd be drinking beer with a Mexican smuggler. Now I am another creature altogether. I am a stay- at-home dad. Allow me an obvious qualification here: It is the patriarch's blessing to watch his baby's eyes slowly transform from black to hazel (the eyebrows come later, in case you don't know). There is the moment when the little beast has figured out how to stand on her own wobbly legs with the help of a chair, or when the first tooth breaks through, or when she mistakenly suckles your nose. These are the good parts. She is 11 months old now and changing fast. I am deeply glad I was there for those things you can never get back once they're gone. But let's not kid ourselves: A man at home with an infant is out to sea without a compass. Confusion and disorientation set in. How much to feed? How much sleep do they need—and when? The baby doesn't know. You sure as hell don't know. And so the little thing shrieks, flushes crimson, gasps for air. You grow frightened. Fear gives way to weariness. Then, like a heel, you close the door and walk away. When my go-to-work wife walks in the door 30 minutes late—after nine hours of me cleaning toilets and washing Claudette's diapers and mopping floors and ruining hand-washables—I'm there at the door to ask her where her priorities are. It's the stuff of daytime talk shows. How did I come to raise a baby? My wife was alone for months at a time while I was scampering around Iraq, or Mexico, or working an investigative piece in a North Carolina slaughterhouse. While I was out for the late-night cocktails, accepting prizes, speaking at prestigious universities, she studied and worked small jobs and never complained. Then, a month after our baby was born last November, my wife's dream job came to her. A middle-school counselor, of all things—that's 500 problems of 500 more kids I've never met. At any rate, what were we to do? My job at the Times was wearing thin; during particularly bad moments I thought I was going to break down: deadline pressure, bland hotel rooms; too many cigarettes and too much coffee; newsroom intrigue, ambition, and ego. It's a noxious mix. My daughter had come unexpectedly early while I was across the continent working on a story. When I was told my wife was in labor, I cried. I was owned by my job and I was lonely. So, shortly after my daughter's birth, I resigned—no leave of absence, no severance package, no gold watch—and off my wife went to earn the mortgage. Becoming a stay-at-home dad seemed noble from the romantic distance of a boy with two stepfathers. Why not? I'm 41. My wife is 37. We'd been waiting our whole lives for a baby to come, and now that she had, what were we to do—fob her off on a stranger before she had taken a step? They say the number of stay-at-home fathers in America has doubled in the past decade, but this statistic gives me no particular pleasure. I'm committed to my decision, but I feel lonely again—only now it's for the old days on the job. It was never a dream of mine to raise a baby. Sometimes, when Claudette is asleep, I find myself staring into the rearview mirror of my career. There was that time in Iraq when I wandered into a city hall that had been taken over by a radical cleric and his followers. It was Good Friday, and in the spirit of brotherhood we prayed together. By the end, the holy man's supporters were chanting with thumbs raised high: "Charlie good! Charlie good!" In some way I was an ambassador—not of the U.S. government, certainly, but at least to the notion that Americans are a decent, brotherly lot. A reporter's job is to write down the history of the living for our grandchildren. Along the way, the reporter gives people things to talk about. He rubs elbows, makes suggestions to people in power, and exposes the wrongs they do. That is what this stay-at-home dad would tell his old self, that young correspondent on the campaign bus. He would also tell that young man that if he gives up his job, his title, his artificial importance, the governor won't be calling anymore; neither will the old colleagues. There will be no more Hollywood parties. No expense account. No action. You will wake up in the morning and do what you did the morning before, I would tell my former self. There will be no sense of accomplishment—at least, not now. You will grow bored. So prepare yourself. It's not the way they tell it in those cute self-help books. It will be just you and the kid. In the mania of my empty house, the afternoon sun bright and debilitating, that old four o'clock hour of deadline adrenaline upon me now, I find myself staring into a dirty diaper as though it were tea leaves, trying to augur some story about the failings of the latest immigration bill. I remind myself at these times that we are in the early stages of a love story, my daughter and I. She is a beautiful little thing: brown wavy hair, alabaster skin, and five little teeth. Her first words were either "Kitty, kitty" or "Hi, daddy." I'm not sure which, but it doesn't matter. I taught them to her and I was there to hear them. When she falls or bangs her head, she cries it out and then crawls on about her business clucking happily. Resiliency. I am teaching her that. She likes people, and people are attracted to her lumpy smile and flailing arms, and that makes me hopeful for her future. She pulls hair at the playground, but we're working on that. She takes naps on my chest. My wife reminds me that if I had kept that power job, I would be watching Claudette grow up through pictures on my cell phone. I am sad for those fathers I had the pleasure to know during the years I was a correspondent. I remember the soldier in Iraq who was not there for the birth of his child. The journalist who came back from the war zone only to be called Uncle by his son. The Mexican man in Long Island, his only presence at home back in the old capital being his photograph and a Western Union receipt. The New York fireman scratching around in the dirt for the body of his son, who died on an unseasonably warm September morning when a skyscraper collapsed upon him. I was mulling this over one workday morning as I drove my daughter to a Mommy and Me yoga class. Me—yoga at noon. To think. "I'm sorry," said the nasally male clerk at the salon desk. "Sorry about what?" I asked. "The class is closed." "The class is closed?" We had arrived early. There was no one else there. "Yes," he stammered. "Closed, uh, well, closed…" "What are you trying to say? Closed to me because I'm not a mommy?" "I'm afraid so. Some women might not feel comfortable." I left without incident. Why shouldn't -women have a club where they could be free from the testosterone of the male interloper? I could have made a scene about the unfairness of it, the double standard—the fact that the golf clubs and fraternal orders have been pried open by women in the name of equality. I could whine on about the birthing classes and prenatal checkup appointments that treat the fathers as only slightly better than a nuisance—a damp dog, more or less. But as Claudette and I leave Yoga World, I'm thinking I really ought to be out there living the big life. I wonder what border my friend Mike is crossing, what glorious trouble might he be getting himself into. I wonder if Mike does yoga. We go off to the park to see the Latina nannies who care for the Little Lord Fauntleroys of a neighborhood filled with two-career families. It's only a 15-minute walk from my own neighborhood, but it's another world altogether. My friend Angelica tells me, "The children love us more than they love their parents. The little one calls me Mommy." Hearing her say it makes me feel less self-centered—and that what I'm doing is important to this little person. I made a promise to my kin and I'm keeping it. My child will never call someone else Daddy. And so we run our epic little routine: Breakfast. Nap. Walk. Church. Park. Lunch. Nap. Bath. Book time. Toy time. Mommy time. Dinner. Bed. Then a nice glass of Pinot for Papa. Still, the ennui must show. A man in my neighborhood who was painting a house stopped painting as he saw me leaning into the perambulator, trying to coax the little howler to sleep. His name was Jose. He was older and wore overalls and paint speckles. This man offered me something so deep, so penetrating, I wrote it down. "The whole world is in your brazos there, amigo," he said, pointing to the carriage. "That little girl is your world and your future and your blood. That is your hair and your eyes—I can see. A man, if he is truly a man, does what God asks him to do. To honor his family." "I know this," I say, fascinated that the stranger could decipher me from across a street. "But it is hard sometimes for me to be happy about it." "Ah. Sometimes you see this duty as women's work?" "Yes," I say. "They must be better at it." "This does not matter," he tells me. "You must be better. If not the woman then the man, yes? This is preferable to the stranger who is not truly able to give the child love." He said it just like that. The nut graph, we call it in journalism. The point of the story. Jose articulated the thing my friends—the go-to-work dads—were not able, or not willing, to tell me: You have to decide if the child is more important than the stature, the action, the money. If she is, you must accept it and get on with the routine. My daughter has awakened. She is standing in her crib, her arms out. "Hi, Daddy," she clucks. Or maybe it's "Kitty, kitty." It doesn't matter, really. She is talking to me. I like this more and more as the days go on. I need her. She has become my purpose. Looking at her now, I know I will return to work someday. We could use the money. And honestly, I need a place in my life that belongs to me. Right now my life is here, but eventually I'll find new places to go. I already know that day will be a sad one. It will be the day my daughter will not need her father so much—anymore—and perhaps by then, her father will not need her so very much either.

|

||||

|

|

|

||