5. The Body in Art and Philosophy

The foregoing has reviewed feminist reflections on art theory, noting how the histories of women in the arts inform contemporary feminist debates and practices. Equally important are assessments of the values that comprise the conceptual frameworks of aesthetics, from which some of the most influential tools of feminist critical analysis emerge.

A good deal of feminist criticism has been focused on eighteenth-century philosophy because of the many influential works on beauty, pleasure, and taste that were written at that time and that became foundational texts for contemporary theories. “Taste” refers to the facility that permits good judgments about art and the beauties of nature. While the metaphor for perception is taken from the gustatory sense, these theories are actually about visual, auditory, and imaginative pleasure, since it is widely assumed that literal taste experience is too bodily and subjective to yield interesting philosophical problems. Judgments of taste take the form of a particular kind of pleasure — one that eventually became known as “aesthetic” pleasure (a term that entered English only in the early nineteenth-century).

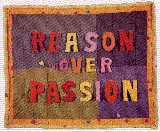

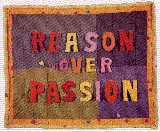

The major theoretical concepts of this period are riddled with gendered significance, although tracing gender in the maze of writings of this time is a task complicated by the unstable role of sexuality in theories of aesthetic pleasure. According to its most austere analysis — which came to dominate aesthetics and philosophy of art — aesthetic enjoyment has nothing to do with sexuality at all: Aesthetic pleasure is not a sensuous, bodily gratification; it is free from practical considerations and purged of desire. The two kinds of desire that most interrupt aesthetic contemplation are hunger and sexual appetite, which are the “interested” pleasures par excellence. Aesthetic pleasures are “disinterested” (to use Kant's term) and contemplative. It is disinterestedness that rids the perceiver of the individual proclivities that divide people in their judgments, and that clears the mind for common, even universal agreement about objects of beauty. Ideally, taste is potentially a universal phenomenon, even though its “delicacy,” as Hume put it, requires exercise and training. To some degree, the requirements of taste may be seen as bridging the differences among people. But there is an element of leisure embedded in the values of fine art, and critics have argued that taste also ensconces and systematizes class divisions (Shusterman 1993; Mattick 1993).

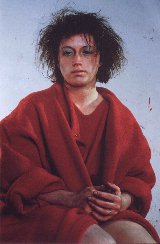

Even as theorists extolled the possibilities for universal taste, however, they often drew gender distinctions regarding its exercise. Many theorists argued that women and men possessed systematically different tastes or capabilities for appreciating art and other cultural products. The most noticeable gender distinction occurs with the two central aesthetic categories of the eighteenth century, beauty and sublimity. Objects of beauty were described as bounded, small, and delicate — “feminized” traits. Objects that are sublime, whose exemplars are drawn chiefly from uncontrolled nature, are unbounded, rough and jagged, terrifying — “masculinized” traits. (These gender labels are unstable, however, for the terrors of nature have an equally strong history of description as “feminine” forces of chaos [Battersby 1998].) In short, aesthetic objects take on a gendered meaning with the concepts of beauty and sublimity. Moreover, so do aesthetic appreciators. As Kant put it in his earlier Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime (1763), a woman's mind is a “beautiful” mind. But a woman is incapable of the tougher appreciation and insight that sublimity discloses. The preclusion of women from the experience of the sublime limits their competence to apprehend the moral and existential weight of the might and magnitude of both nature and art. The aesthetic pleasure of the sublime is paradoxically founded on terror. Women's supposed weaker constitutions and moral limitations, as well as their social restrictions, contributed to a concept of sublimity that marks it as male. Debates over the nature and concept of sublimity gave rise to feminist debates over whether one can discern in the history of literature an alternate tradition of sublimity that counts as a “female sublime” (Freeman 1995, 1998; Battersby 1998).

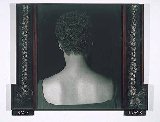

The careful purging of sensual pleasure from aesthetic enjoyment mingles with the paradoxical employment of female bodies as examples of aesthetic objects. Among the things that are naturally agreeable to human nature, Hume lists music, good cheer, and “the fair sex.” And Kant states, “The man develops his own taste while the woman makes herself an object of everybody's taste.” (Kant 1798/1978, p. 222) Edmund Burke frankly eroticizes beauty when he speculates that the grace and delicacy of line that marks beautiful objects are reminiscent of the curves of the female body (Burke 1757/1968). If women are the objects of aesthetic pleasure, then the actual desire of the perceiver must be distanced and overcome in order for enjoyment to be purely aesthetic. This outcome is one implication of the notion of disinterested pleasure. This requirement, it would seem, assumes a standard point of view that is masculine and heterosexual. But of course women are also subjects who exercise taste. This implies that women are unstably both aesthetic subject and object at the same time.

Disinterestedness has a long history; it characterizes the popular aesthetic attitude theories of the twentieth century, which argued that a prerequisite for any kind of full appreciation of art is a distanced, relatively contemplative stance towards a work of art. Similar assumptions about the most suitable way to view art lie behind the formalist criticism that dominated visual art interpretation for decades, and that also characterize interpretive norms in other art forms such as literature and music (McClary 1991, p. 4; Devereaux 1998; Brand 2000). The value of disinterested aesthetic enjoyment has come under heavy critical scrutiny on the part of feminists, who have deconstructed this idea and argued that a supposedly disinterested stance is actually a covert and controlling voyeurism.

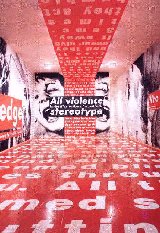

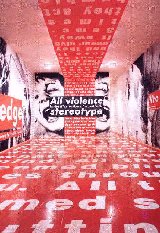

Criticisms of theories that mandate this sort of distanced enjoyment have given rise to influential feminist theories of the perception and interpretation of art. The type of art that has come in for particular scrutiny in terms of the implications of disinterested enjoyment is visual art, and a good deal of argument about what has become known as “the male gaze” has been produced from film theorists and art historians, and subsequently investigated by philosophers. The phrase “male gaze” refers to the frequent framing of objects of visual art so that the viewer is situated in a “masculine” position of appreciation. By interpreting objects of art as diverse as paintings of the nude and Hollywood films, these theorists have concluded that females depicted in art are standardly placed as objects of attraction (much as Burke had lined up women as the original aesthetic object); and that the more active role of looking assumes a counterpart masculine position. As Laura Mulvey puts it, women are assigned the passive status of being looked-at, whereas men are the active subjects who look (Mulvey 1989). Art works themselves prescribe ideal viewing positions. While many women obviously also appreciate art, the stance they assume in order to appreciate works in the ways they were intended requires the donning of a masculine perceptual attitude.

Theories of the male gaze come in several varieties: Psychoanalytic theories dominate film interpretation, (Mulvey 1989; Doane 1991); but their presumptions and methodology are contested by philosophers more attuned to cognitive science and analytic philosophy (Freeland 1998a; Carroll 1995). Versions of the male gaze can be found in the existentialist feminism of Simone de Beauvoir (Beauvoir 1953); and there are empirically-minded observations that confirm the dominance of male points of view in cultural artifacts without adopting any particular philosophical scaffolding. These theories differ in their diagnosis of what generates the “maleness” of the ideal observer for art. For psychoanalytic theorists, one must understand the operation of the unconscious over visual imagination to account for the presence of desire in objects of visual art. For others, historical and cultural conditioning is sufficient to direct appreciation of art in ways that privilege masculine points of view. Despite many significant theoretical differences, analyses of the gaze converge in their conclusion that much of the art produced in the Euro-American traditions situate the ideal appreciator in a masculine subject-position. There is debate over the dominance of the male-position in all art, for appreciative subjects cannot be understood simply as “masculine” but require further attention to sexuality, race, and nationality (Silverman 1992; hooks 1992). Sometimes a facile reading of the gaze tempts one to exaggerate the sharpness of gender distinctions into the male viewer and the female object of the gaze, though most feminists try to avoid such reductionism. Despite their differences, theories of the gaze reject the idea that perception is ever passive reception. All of these approaches assume that vision, the quintessential aesthetic sense, possesses power: power to objectify — to subject the object of vision to scrutiny and possession. The male gaze has been a theoretical tool of inestimable value in calling attention to the fact that looking is rarely a neutral operation of the visual sense. As Naomi Scheman states: