5. The Body in Art and Philosophy

Feminist analyses of aesthetic practices of the past have influenced the production of feminist art of our own times, and the latter in turn has contributed to a dramatic alteration of the climate of the art world. The changes that have beset the worlds of art in the twentieth century, perhaps most dramatically in the fields of the visual arts, are frequently the subject of philosophical discussions in the analytic tradition regarding the possibility of defining art (Danto 1988; Davies 1991; Carroll 2000). One challenge to defining art stems from the fact that contemporary artists frequently create with the intention of questioning, undermining, or rejecting values that defined art of the past. The early and mid-twentieth century extravagances of Dada and Pop Art are most often the target of philosophical inquiries, which seek to discover commonalities among artworks that have little to no perceptible defining similarities.

As we have seen, the category of fine art has been a focus of feminist scholarly scrutiny because its attendant values screened out much of women's creative efforts or actively dissuaded their attempts to practice certain genres. However, the dissolution of the values of fine-art long preceded the art scene that second-wave feminists entered in the 1970s. In spite of sweeping changes in the concepts of art and its purposes that characterize much art of the last century, the numbers of women practitioners in arts such as painting, sculpture, and music, remained small. Therefore, while fine art may have historical importance for women's artistic influence, it clearly was not the perpetuating cause of their exclusion from the worlds of art. The anti-art and avant garde movements so frequently discussed by contemporary analytic philosophers were just as male-dominated as classical music or Renaissance sculpture. Moreover, values surrounding the artistic “genius” were just as vigorous as ever. Therefore, feminist art practices began as activist movements to secure women more visibility and recognition in the artworld. Feminist artists not only demanded that their work be taken seriously, in their works they mounted a critique of the traditional thinking that lay behind their exclusions from the powerful centers of culture.

For these reasons, feminist art itself also furnishes numerous examples that subvert older models of fine art, but with added layers of meaning that distinguish it from earlier iconoclastic movements. Because of the gendered significance of the major concepts of the aesthetic tradition, feminist challenges often systematically deconstruct the concepts of art and aesthetic value reviewed above. Feminist art has joined — and sometimes has led — movements within the artworld that perplex, astound, offend, and exasperate, reversing virtually all the aesthetic values of earlier times. As art-critic Lucy Lippard put it, “feminism questions all the percepts of art as we know it” (Lippard 1995, p. 172). Feminist artists have challenged the ideas that art's main value is aesthetic, that it is for contemplation rather than use, that it is ideally the vision of a single creator, that it should be interpreted as an object of autonomous value (Devereaux 1998). Feminism itself came under internal criticism for its original focus on white, western women's social situations, a familiar critique in feminist circles that has a presence in aesthetic debates. By the late twentieth century, the energies of feminist and postfeminist artists of diverse racial and national backgrounds have made the presence of women in the contemporary artworld today powerful and dramatic.

In many discussions of contemporary art, “feminist” art is a label for work produced during the active phase of second-wave feminism from the later 1960s to about 1980. The term “postfeminist” is now in use for a subsequent generation of artists who pursue some of the ideas and interests of the earlier period. These terms are far from precise, and there are many artists practicing today who continue to identify themselves with the term “feminist.” Perhaps an even larger group does not attend particularly to labels, but their work is so provocative about the subject of gender and sexuality that it has become a focus for feminist interpretation. (The photographic art of Cindy Sherman is a case in point.)

In brief, feminist artists share a political sense of the historic social subordination of women and an awareness of how art practices have perpetuated that subordination — which is why the history of aesthetics illuminates their work. The more politically-minded artists, especially those who participated in the feminist movement of the 1970s, often turned their art to the goals of freeing women from the oppressions of male-dominated culture. (Examples of such work include the Los Angeles anti-rape performance project of Suzanne Lacy and Leslie Leibowitz, In Mourning and in Rage (1977) and Womanhouse (1972), a collaboration of twenty-four artists.) Feminist artists opened up previously taboo subjects such as menstruation and childbirth for artistic presentation, and they began to employ female body images widely in their work. All of these moves were controversial, including within the feminist community. For example, when Judy Chicago made her large collaborative installation “The Dinner Party” in the early 1970s, she was both praised and criticized for the thematic use of vaginal imagery in the table settings that represented each of thirty-nine famous women from history and legend. Critics objected that she was both essentializing women and reducing them to their reproductive parts; admirers praised her transgressive boldness.

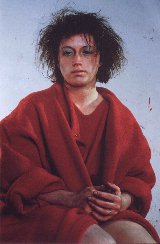

Postfeminists artists build upon the efforts of their predecessors in exploring the body, gender, and sexual identity. Postfeminist art, often highly theoretical and deeply serious, also tends to be playful and parodic in style; it is less overtly political than the art of earlier feminists. Influenced by postmodern speculations that gender, sexuality, and the body itself is a creation of culture that is malleable and performative, postfeminist art confounds and disrupts notions of stable identity (Grosz 1994; Butler 1990, 1993). It can be seen as individualistic compared to the social agendas of feminism, and perhaps for this reason this sort of art is also more attuned to differences among women. Their presentations of the female body tend to draw attention to the position it has in culture: not only the sexed body, but also bodies marked by racial and cultural differences. All of this activity is theoretically-charged and often philosophically motivated (Reckitt 2001).